What is colic?

The term “colic” is defined as a general manifestation of abdominal discomfort in the horse, regardless of the cause.

While most cases of colic are associated with gastrointestinal disturbances, the nature of some abdominal discomfort may be non-gastrointestinal in origin, such as those resulting from other abdominal organs (including but not limited to the liver, spleen, ovaries, or kidneys).

Colic is classified as abdominal pain or pain within the digestive tract due to a gastrointestinal disturbance.

Colic is not a disease but a group of symptoms.

Classification / types of equine Colic

Anatomical: -

1.

True colic and

2. False colic

Etiological colic: -

1.

Physical colic and

2.

Functional colic

Clinical colic: -

1. Spasmodic colic

2. Tympanic colic

3. Obstructive colic

4. Extra-luminal colic

Based on duration of the disease

1. Acute: <24-36hrs

2. Chronic: >36hrs

3. Recurrent: multiple episodes separated by periods of >2days of normality.

% of Various Type of colic reported on a farm based survey

Non-specific diagnoses 64% 1

Impactive/acute intestinal obstructive colic 17%

Spasmodic colic 9%

Sand colic 5%

Gas colic 3%

Verminous mesenteric arteritis 1%

Enteritis due to ingestion of moldy grain 1%

Risk Factor

Identified a number of factors that are associated with increased risk of colic are

The intrinsic factors of horses (age, breed & sex)

Parasite Burden

Certain feed types

Recent change in feeding practices

Stabling

Lack of access to pasture and water

Increasing exercise and transport

Daily feeding of concentrate > 5 kg/day to horses increased the risk of colic.

Feeding more than twice daily increased the risk of colic.

Feeding ≥ 50% of the diet as alfalfa, feeding <50% of the diet as oat hay and lack of daily access to pasture grazing are found to be significantly associated with Colic.

Activity:

Decreased in regular exercise or changing from turn out activity to strict stall confinement increased risk of cecal and large colon impaction.

Transport >24 hours increased risk of simple colonic obstruction or distension.

Cribbing behaviour may increase the risk of simple colonic obstruction or distension.

Parasites:

Parascaris equorum causes the Small intestinal obsruction without infarction.

Anoplocephala perfoliata increased risk of bowel irritation, ileal impaction and spasmodic colic.

Large strongyle worms, most commonly Strongylus vulgaris, are implicated in colic secondary to non-strangulating infarction of the cranial mesenteric artery supplying the intestines.

Pathophysiology

Simple

obstruction

Trapping

of fluid within the intestine

The

large amount of fluid produced in the upper gastro-intestinal tract

This is

primarily re-absorbed in parts of the intestine downstream from the

obstruction.

This

degree of fluid loss from circulation leads decreased plasma volume leading to

a reduced cardiac output and acid-base disturbances.

Intestine

distention due to the trapped fluid and by gas production from bacteria

Activation

of stretch pain receptors leads to the pain

With

progressive distension there is occlusion of blood vessels, firstly veins then

arteries.

Impairment

of blood supply

Leads

to hyperemia and congestion and ultimately to ischemic necrosis and cellular

death.

Leading to an increased permeability.

In the

opposite fashion gram-negative bacteria and endotoxins can enter into the

bloodstream leading to further systemic effects

Obstructive

+ Strangulating

⇓

Distention loss of barrier function

⇓

Impairment of blood Supply

Critical reduction in

blood flow and tissue perfusion leads to tissue hypoxia/ ischemia

Epithelial cells

begin to loosen at villus tip lead to Necrosis

Cardiovascular

collapse & Endotoxemia

Inflammation

Increase GI motility

and decrease absorptive function (causing diarrhoea)

Accumulation of fluid

and ingesta

Distention

Abdominal pain due to

stretching of the wall

Symptoms of Colic

Loss of appetite

Increased pulse rate

Excess salivation

Frequent attempts to urinate or defecate

Abdominal pain

Pawing

Stretching

Flank watching

Biting the stomach

Decreased faecal

output

Repeated lying down

and rising

Rolling

Categorization of abdominal pain

On the basis of the duration of action

Per

acute: <

1 hr

Acute:

<

24 hrs

Subacute:

24-72

hrs

Chronic:

>

72 hrs

On the basis of Character

Recurrent

Occasional

Intermittent

Continues

On the basis of the intensity

Mild

Moderate

Severe

Diagnosis

History and Clinical findings

Physical examination

Auscultation and percussion

Rectal examination

Nasogastric

intubation

Laboratory tests

Radiography

Ultrasonography

The described approach to colic workup is based on the

“10 P’s” of Dr. Al Merritt. You can use whatever approach you want. But, find

what works best for you then stick with it.

1. PAIN – degree, duration, and

type

2. PULSE – rate and character

3. PERFUSION – mucous membranes,

skin tent, jugular fill, etc.

4. PERISTALSIS – gut sounds, fecal

production

5. PINGS – simultaneous

auscultation/percussion

6. PASSING A TUBE – amount and character

of reflux, ifpresent

7. PALPATION – rectal exam

8. PAUNCH – a word for obvious

abdominal distention thatbegins with “P”

9. PCV/TP

10. PERITONEAL FLUID

History & clinical findings

History & clinical findings it gives clue for treatment, causes and whether the horse requires surgery.

Feeding practices, exercise, deworming, past episodes of colic and treatment given.

Respiration rate is

<

40/

min. in mild colic.

Up to 80 / min. in sever

colic.

>

120/min.

in terminal stage of colic.

Auscultation

Continuous and loud bolborygmi - Intestinal

hypermotility (Spasmodic colic, early

Absence or brief with Splashing

Character - ileus

Pinging sound - Small or large colon impaction,

gas colic or colon displacement, torsion of colon or cecum

The

heart rate gives a very good indication of severity of the colic and it also

gives a good idea of prognosis.

The more serious colic having very elevated heart rates.

Nasogastric intubation.

Passing a

Naso-Gastric Tube (NGT) is useful both diagnostically and therapeutically.

Diagnosis (

e.g.. Proximal bowel obstruction, gastro-duodenal ulcer, large colon

displacement)

Analgesia

Prevention of

gastric rupture

Administration of medication

In

general, gastric reflex up to 2 lit.

If excess Gastric out flow problem

Colour:-

Green or Brown Normal

Yellow S.I. reflex

Orange Haemorragic intestinal disease.

pH:-

4-6

Normal

6-8 Reflex from S.I.

Foul-smelling, fermented or copious bloody reflux is associated with anterior enteritis.

With intestinal obstruction, the reflux is usually composed of fresh feed material and intestinal secretions.

Reflux originating from the small intestine is alkaline whereas reflux composed of gastric secretions is acidic.

Rectal palpation

The rectal palpation helps to diagnose the type of colic which can be used to determine the treatment.

Rectal palpation helps to diagnose uterine torsion, viscus distension ( by gas, fluid or feces), large bowel displacement and dilated small intestinal loops.

The most important questions to answer when performing a rectal examination are:

Is visceral distention

present?

If so, which segment (i.e. large colon, small colon, cecum, or small

intestine) is distended?

What is the nature (i.e. fluid,

feed, gas, solid object) and severity (mild, moderate, severe) of the

distention?

Answers to these basic questions will provide diagnostic and/or therapeutic information for the majority of horses with colic, even if a specific lesion is not identified.

Abdominocentesis

The extraction of fluid from the peritoneum can be useful in assessing the state of the intestines.

Radiography:

Abdominal radiographs used to diagnose the colic due to

Enteroliths and Sand impaction.

The abdomen radiography is divided into 3 regions using

the following techniques:

Cranial (140 kvp, 120 mAs, 500 mA)

Mid abdomen (140 kvp, 160 mAs, 500 mA)

Caudal aspect (140 kvp, 100 mAs, 500 mA).

Laboratory tests

Increase PCV and TP Indicate

dehydration.

Complete blood count

Proximal Entritis –

leucocytosis with left shift,

Peritonitis – leucocytosis

& increase fibrinogen concentration.

Endotoxaemia – marked

leucopenia

Serum electrolyte profile

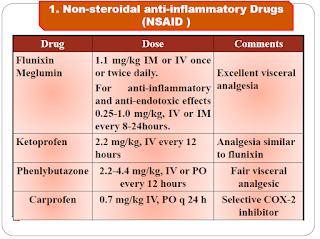

Medical management of colic

Most causes of colic can be managed medically only a 4% to 10% require

surgery.

The decision whether a colic case should be managed medically

or surgically depends on 5 main points.

Severity of pain (responsive vs. Nonresponsive to analgesia),

Cardiovascular and systemic status

Findings on transrectal palpation

The presence of nasogastric reflux

Results of abdominocentesis

Treatment outline:

Correction of pain

Hydration therapy

Replacement therapy,

Maintenance therapy

Other therapy

Antibiotics

Lubricants

Fecal softeners

Promotility agents

Antiulcerative therapy

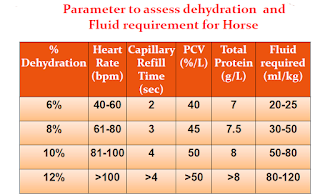

Fluid therapy plan

Correction of dehydration:

Estimate of dehydration (%) x body

weight (kg)

Volume of fluids to give:

Maintenance requirements + Correction of

dehydration + Ongoing losses

For example,

A 500 kg horse that is 6% dehydrated would require approximately 30 liters to correct the fluid deficit.

Maintenance fluid requirements for the adult horse are approximately 50-60

ml/kg/day or approximately 25-30 liters per day.

As an example, assume you are presented with

a 500 kg horse afflicted with colitis. The horse has had diarrhea for 2 days,

is off feed, and clinical examination findings result in an estimate of

moderate (7%) dehydration.

A plan for the initial 12 hours would be formulated as

follows:

1. Rehydration needs: 0.07 (estimated 7% dehydration) x 500 kg = 35 kg ≈

35 lit.

2. Maintenance needs: 50 mL/kg/24 h x 500 kg = (25,000 mL/24 hours)/2 =

12.5 lit.

3. Ongoing losses: estimated at 2 lit./h x 12 h = 24 lit.

TOTAL:

35 + 12.5 + 24 = 71.5 lit.

1. Dehydration

fluid deficit in liters:

Equal to the weight of the horse in kilograms times the

percent dehydration.

2. Daily

maintenance needs of the horse in liters:

60 ml/kg/day (adult)

70-80 ml/kg/day (foal)

3. Fluids needed

for ongoing losses:

Such as fluids lost in diarrhea or nasogastric reflux.

Combination of clinical signs and basic laboratory

tests can be used to assess hydration.

69

The composition of the fluids to be administered

should be selected based upon the most likely fluid and electrolyte needs and

upon results of a chemistry profile.

Frequently, a balanced polyionic fluid, such as

lactated or acetated Ringers, is appropriate. However, sometimes it is

necessary to administer other types of fluids.

The most common electrolyte abnormalities that develop

are hypokalemia and hypocalcemia; these are often exacerbated by administration

of high volumes of IV fluids, particularly in horses that are not allowed to

eat.

Horses with gastric reflux often develop hypochloremic

metabolic alkalosis; these horses should probably be administered 0.9% NaCl

with KCl.

The most common acid-base disturbance encountered is metabolic acidosis,

which occurs as a consequence of lactic acidosis secondary to hypovolaemia

and/or endotoxaemia, or of hyponatraemia secondary to colitis, peritonitis or

gastrointestinal torsion.

Metabolic alkalosis occurs as a consequence of hypochloraemia secondary

to high volume gastric reflux or of hypoalbuminaemia.

Treatment should be aimed at the underlying cause, thus, lactic acidosis

should be treated with a large volume of polyionic fluids, hyponatraemia with

normal or hypertonic saline, hypochloraemia with normal saline and

hypoalbuminaemia with colloids.

Prevention:

Maintain a regular feeding schedule.

Ensure constant access to clean water.

Provide at least 60% of digestible energy from forage.

Do not feed moldy hay or grain.

Feed hay and water before grain.

Provide access to forage for as much of the day as possible.

Do not over graze pastures.

Do not feed or water horses before they have cooled out.

Maintain a consistent exercise regime.

Control intestinal parasites through periodical deworming programme.

Sources:

https://lacs.vetmed.ufl.edu/files/2011/12/Equine-Colic-and-GI-Diseases.pdf

https://secure.caes.uga.edu/extension/publications/files/pdf/B%201449_1.PDF

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15631904/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242192389_Colic_prevalence_risk_factors_and_prevention

https://nurseslabs.com/nasogastric-intubation/

https://www.slideshare.net/hamedattia1/colic-in-equines-prof-dr-hamed-attia-74345874

Post a Comment